Content Warning: This post is about the work that we are doing to protect young women, ages 9-13, from FGM. It is a serious, shocking subject. I hope that I can shed a little light on why this awful practice continues, as well as offer some hope that it will slow down and eventually stop.

This past December, we protected 95 young women from the FGM rituals by hosting them at a safe location for 20 days and nights. When I say “we”, I mean that The Emmanuel Center for Women and Children worked together with me and my community here at QuadW Tarime, while The Sunflower Foundation in Melbourne, Australia provided the majority of the funding. I can’t possibly credit all of the Kuria and Tanzanians who have joined together in fighting this, but a few names, listed alphabetically: Anna Migera, Dinnah Sylvester, Doto Francis, Gloria Sentozi, Happiness Wikendi, Mwita Baita, Pili Nyangi, Raphael Musa, Rhoby John, Sarah Sabai, Sarah Wambura, Simeon Mwita, Wikendi Juma, Veronica Marwa Rhodes.

What exactly is the practice? Here in Tarime, the Kuria tribe holds a religious ritual called the tohara where they clear a field about twice the size of a football field and ask all of the families within several miles to send their daughters who have recently gone through puberty. The tribal elders and the waangariba (the ones who do the cutting) sacrifice a strong, healthy bull to the 8 Great Spirits and then blow milk through the bull’s horns. Then the cutting begins.

Girls begin to arrive and are told to stand naked, in a line, until the first one is called for. She goes to the waangariba, alone, pays the required twenty dollars and hands them her razor blade. Two of them hold her thighs while the third removes her clitoris with the razor blade. She is told not to stop the bleeding, because her blood is an offering to the 8 Great Spirits. Then one of the tribal elders throws flour on her now-mutilated vagina, throws flour on her face, and wraps her in a kanga, a traditional wrap skirt. At the exit, some of her family members are waiting for her. They walk her down many of the streets of the village, waving tree branches, blowing whistles, and singing celebratory Kuria songs. When she finally arrives at home, she is showered with gifts, money, and expensive foods. Neighbors and distant family members show up and give livestock and other gifts to her family, to celebrate their daughter being cut.

We estimate that somewhere between 600 and 1,800 girls are cut during each year that the ritual is performed, and some small percentage of these girls die due to blood loss and infection; I don’t have exact numbers on this.

I say, “here in Tarime” because FGM is done very differently in Somalia, Egypt, Sudan, the Middle East, and the countries in West Africa.

The ritual is deeply religious. At some point in November, the chief of the tribal elders says that he has received a message from the 8 Great Spirits about when the cutting is to begin, and when it is to end. During that time, the tribal elders and the waangariba are strictly forbidden from showering, farming, carrying water, wearing red, burying any dead, attending any funerals, leaving the Tarime area, and slaughtering any animals (aside from the sacrificial bull). When they reach the day when the cutting is to end, everyone takes a shower, and then the 8 Great Spirits forbid them from cutting any more girls for another two years.

When I first heard about this practice, I could hardly believe that it was real. I was even more puzzled when I realized that the Seventh-Day Adventist, Catholic, and Anglican Churches arrived in full force in the 1960s and attracted large numbers of Kuria members. Pentecostal Churches started popping up in the 1980s and were willing to go to even more rural areas, on lower budgets, than the more institutional denominations. With so many churches, why had such an unloving, harmful, superstitious practice been allowed to continue?

I was further disappointed this past year. We are working to increase the number of girls who we can protect in 2024 and the coming years, so we started doing research and trying to make contacts in Kuria villages that we had never been to before. In these new villages, an obvious place to start was with the churches. But as we went from village to village, and church to church, we learned that many of the church leaders continue to send their daughters to the cutting.

But being from Alabama, I could not help noticing the similarity to an equally bizarre practice; owning human beings, treating them like animals and using them for farm labor, and claiming that this was a good thing due to them having a bit darker hue of skin.

In both cases the practice is bizarre; an outsider couldn’t make heads or tails of it. In both cases, the practitioners identify with Jesus Christ, a man whose life and death were all love; only love; a man who never harmed anyone, and who never held anything back for himself.

In both cases, the practice slowly decreased in power, mainly through the intervention of outsiders. We know about how it took a tragic and bloody war to abolish slavery, and how its practitioners developed new systems of prison slavery, sharecropping, and segregation to keep some semblance of slavery going even after it had been formally abolished. Though these systems have slowly become less pronounced, they still exist, and continue to devour the lives of countless real people every year, while making countless others miserable. (Here I’m referring to those who are given long sentences for minor drug infractions, who are given far longer sentences than their white counterparts for the same crimes, or who lose their lives to police brutality, as well as many other forms of race-based oppression that continue to thrive.)

The practice of FGM is steadily dying. I know many Kuria women who were able to get a good education and delay marriage; none of them have had the practice performed. People from other tribes now intermarry with the Kuria and this steadily decreases the power of the practice. It is also illegal; at least two practitioners were arrested in the Tarime area during the cutting season last year.

As myself and my (mainly Kuria) team researched ways to protect girls and weaken the practice, we found another shocking parallel. We wondered if we might be able to go directly to the tribal elders and the waangariba and simply persuade them to stop. We knew of a woman who had been one of the waangariba, but who had decided to stop and follow Jesus. So we went to her house and asked her if it might be possible to persuade others, too. She shook her head sadly, and she said that she had been trying for years. Their reply was always the same: “What else could we do that would make this much money?”

This made sense of something that we had seen last year. Originally, the tribal elders had announced that the 8 Great Spirits had told them that cutting season would be December 9th until December 24th. We understood the decree of the 8 Great Spirits to be set in stone, unchangeable. But around December 22nd, we heard that the 8 Great Spirits had changed their minds, and cutting season could continue until December 29th. Some of our Kuria team laughed cynically when they heard the news. “C’mon, the tribal elders always do like this. If they see they haven’t gotten money enough, they say the 8 Great Spirits have changed their ideas. They add more days so they can get more money.”

In both cases we see a practice that oppresses a large group of real people. In Alabama, slavery oppressed people of a darker skin color; in Tarime, FGM oppresses women. In both cases, greed keeps the practice alive. Greed motivates the oppressors to see this group as less human. And because they see this group as less human, they feel comfortable and justified in going farther with their greed. Last year during the camp, we protected a girl who was 5 years old. I asked why, since she hadn’t gone through puberty. I was told, “That girl… she doesn’t really have parents. During the daytime, she runs all over the place, playing with other girls. Normally, it’s fine, but during cutting season, these elders, they want more money. They’ll find her, entice her, cut her, and then find a distant relative and make them pay the twenty dollars.”

In both cases, change comes slowly. We start churches, we become members, we say that we want to follow Jesus, but we stop short of unconditional love for all. We embrace the elements of Jesus that are easy for us to embrace; when he challenges the harmful vestiges of our own culture, we ignore him, or rationalize it away.

It’s the same question that I ask myself as I re-read the gospels of Matthew, of Mark, of Luke, of John. Do I live like Jesus? If Jesus was in my position, how would he live? How would he love? How would he deal with the tangled dilemmas that present themselves to me every day; how to love every person fully with limited resources; especially limited time, the most limited resource of all?

When am I choosing Jesus, and his way of unconditional love? When am I choosing to hang on to some of the harmful vestiges of my own culture? Do I see my harmful attitudes as normal, because they are just the water that I’ve been swimming in for so long?

One of my favorite authors reminds us,

“In the hands of the oppressor I recognize my own hand. Their flesh is my flesh, their blood is my blood, their pain is my pain, their smile is my smile. Their ability to torture is in me, too.”

– Henri Nouwen

Just as the Kuria Christians, or my great-great-grandparents, need to examine their own faith and admit that this practice is not something that Jesus would participate in, I also need to look for where my hand is the hand of the oppressor, or where my hand is becoming the hand of the oppressor, by slow, seemingly minor changes in my habits. Where am I hurting the people around me? Where am I making things harder on them? What are the long-term consequences of my habits?

I’m thankful for a small group of committed, thoughtful Kuria disciples at the Emmanuel Center and at QuadW Tarime who have chosen to examine themselves, and who have decided to choose Jesus, rather than the harmful vestiges of their own culture.

In 2023, there is no cutting ritual, so we are using this opportunity to educate the girls. We learned in 2022 that many girls go to the cutting because of the disinformation that is spread by the adults; some of the most common lies are that it is just a tiny, superficial cut, and that the clitoris grows back. From December 8th to December 21st, we will host 150 girls, overnight, at the Emmanuel Center Primary School. We will teach them in detail what the cutting is, that it is irreversible, the risk of death, how to stand up to peer pressure, and how to share the truth with other girls.

During the coming year, we will spend time getting to know government officials, pastors, and respected elders in villages around Tarime, doing our best to find as many people as we can who are actively opposed to the practice. These faithful few will help us to identify the girls who are in danger.

And then, when the cutting rituals take place again in 2024, we will protect 300 girls, as we join in sweeping this practice away.

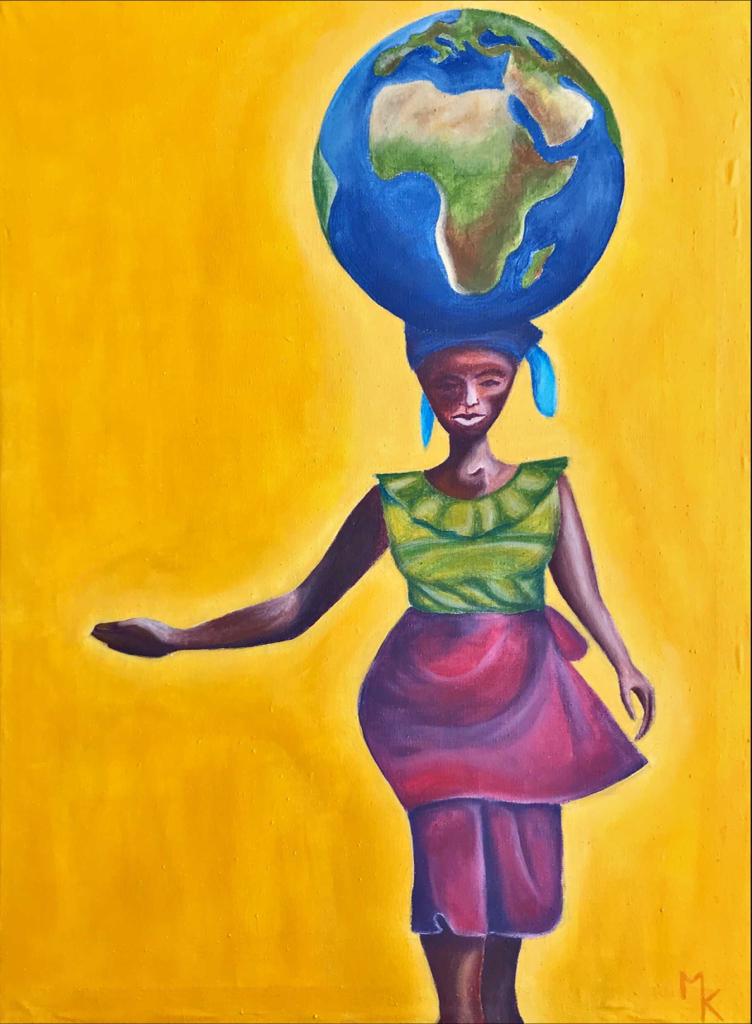

As they let go of this practice, I wonder if the Kuria people will become more Kuria, not less so. The title of this post is a beautiful Swahili word that means “deliverance”. I’m looking forward to the majesty that will be unfolded when the brave, proud, Kuria women are delivered from their oppression and free to be their real, Kuria selves.

You can make more of this happen by donating to QuadW Tarime (tax-deductible) at:

https://www.wesleycollegetzfoundation.com/donate

Or to The Emmanuel Center (tax-deductible) at:

https://advance.umcmission.org/p-495-emmanuel-center-for-women-and-children-tarime.aspx

Or to The Sunflower Foundation (tax-deductible) at:

https://www.paypal.com/donate/?hosted_button_id=EYN7JEBDDD5AQ